Don’t let zombies eat your readers’ brains

Like humans, metaphors have life spans. They’re born; they live full, productive lives; they grow old; they die. They’d even stay dead, if we’d let them.

But too often, writers drag these literary corpses around for so long, they start to really stink up our messages.

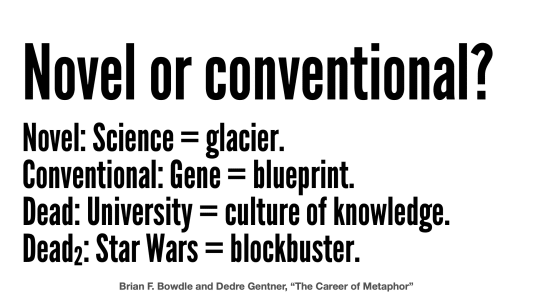

One solution: Make sure you know the difference between novel, conventional, dead and dead2 (that’s really, really dead) metaphors. Researchers Brian F. Bowdle and Dedre Gentner explain it all to us in “The Career of Metaphor” (PDF).

1. Metaphors are born.

Metaphors are figures of speech. When they are born, they’re called novel metaphors.

Here’s a novel metaphor:

Science is a glacier.

Readers understand the literal meaning of glacier: “a large body of ice spreading outward over a land surface.” And while we’re not familiar with the metaphorical sense, we understand that it means something that “progresses slowly but steadily.”

Readers take longer to process novel metaphors than any other kind. And that processing time pays off.

Novel metaphors open new avenues of thought for readers. If love is a rose, for instance, could jealousy be a weed? That might help you extend your metaphor throughout the body of your essay.

2. They live full, productive lives.

Metaphors in their prime are called conventional metaphors.

Here’s a conventional metaphor:

A gene is a blueprint.

Readers understand the metaphorical meaning — “something that provides a plan” — in part before they’ve heard it before.

Because of that familiarity, readers take less time processing conventional metaphors than novel ones.

Conventional metaphors read more like comparisons or categorizations. For instance, if the sun is a tangerine, readers understand that both belong to groups of things that are round and things that are orange.

However, categorical metaphors are less likely to generate semantic shifts or additional meanings. (And, like a tangerine, the sun makes a refreshing, healthy snack on a hot day …)

3. They die.

Academics call dead metaphors dead1 metaphors. Because of course they do.

Here’s a dead1 metaphor:

A university is a culture of knowledge.

Here, readers lose the literal meaning: We assume the word culture refers to a particular heritage or society.. But in fact, in this metaphor, culture refers to a bacteria culture, aka “a preparation for growth.”

However, because of overuse or time, neither of these meanings seem related to universities. (Overused metaphors: time is running out, flying off the handle, head over heels, max black.)

There’s another word for dead1 metaphors: cliché.

4. And they get really, really dead.

Then there are really, really dead metaphors — aka dead2 metaphors.

Here’s a dead2 metaphor:

“Star Wars” was a blockbuster.

These historical metaphors have lost the meaning of the original metaphor altogether. Today, blockbuster seems to mean “anything that is highly successful.”

But back in the day, blockbuster referred to a bomb that could demolish an entire city block.

Dead1 and dead2 metaphors don’t give readers any new way to think about the topic. They take up space without adding meaning.

Write novel metaphors.

So which type of metaphor works best?

Two researchers reviewed 41 data-based studies on the persuasiveness of metaphor published between 1952 and 2006. Then they analyzed the studies to determine what made metaphors more or less persuasive.

Among their findings: More novel metaphors were more persuasive (effect size: .129) than conventional metaphors or clichés (.008).

“We uncovered only two instances out of 14 in which the use of metaphor might be detrimental to the goal of generating agreement with the message advocacy,” the researchers says: putting the metaphor at the end of an argument and using clichés.

Don’t let literary zombies eat your readers’ brains. Cut clichés — and replace them with novel metaphors.

___

Sources: Brian F. Bowdle and Dedre Gentner, “The Career of Metaphor,” Psychological Review, 2005, Vol. 112, No. 1, 19 3-216

Pradeep Sopory and James Price Dillard, “The Persuasive Effects of Metaphor: A Meta-Analysis,” Human Communication Research, January 2006

Leave a Reply