Is this approach still a grammar don’t?

It may be the most famous split infinitive of all time — Star Trek’s opening-sequence voice over:

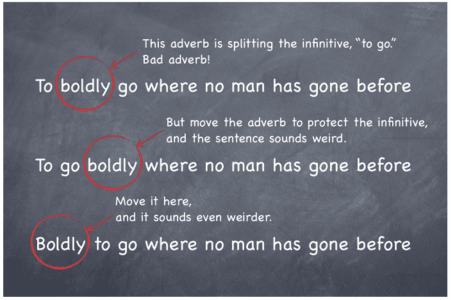

“To boldly go where no man has gone before”

That’s a split infinitive, because the adverb “boldly” separates, or splits, the verb “to go.”

So, is that OK? Are split infinitives acceptable in modern English usage? Or does good writing demand that we keep our infinitives married?

To find out, I turned to my BFF and grammar tutor Wikipedia. Bottom line, according to the grammar gurus who put the “Split infinitive” page together?

“Most modern English usage guides have dropped the objection to the split infinitive.”

But there’s more to that story. Because historically, experts debated whether writers could properly split infinitives. Some believed — and still do — that split infinitives made sentences clearer and more elegant.

Lickity split: History of the split infinitive

A Mesopotamian first picked up a stick and wrote a word in 3200 B.C. But it wasn’t until the Middle Ages, according to linguists, that the first infinitive was split. During the Renaissance, the practice of infinitive-splitting lost favor — though William Shakespeare did split one:

Split infinitives reappeared in the 18th century and became more common in the 19th.

It wasn’t until 1897, though, that the term “split infinitive” emerged, followed in the 1920s by “infinitive-splitting” and “infinitive-splitter.”

Religious divide: The infinitive-splitting debate

Rules against infinitive-splitting emerged in the mid-19th century. Among them:

1. It’s not the Queen’s English. Aka “our teacher told us not to.”

2. It’s a single verb. “To go” is the verb. Not “to” or “go.” Can’t divide that verb.

3. It’s based on Latin. “The Victorian Era was a time of great language debate with dueling dictionaries and people pontificating about language,” writes Grammar Girl Mignon Fogarty. “The conventional wisdom is that people decided that because infinitives can’t be split in Latin, they shouldn’t be split in English.”

This belief, writes Richard Bailey, “is part of the folklore of linguistics.”

From the beginning, rules against splitting infinitives were controversial. Authors of grammar texts argued that splitting infinitives was no crime and in fact often made sentences clearer.

Splitters and anti-splitters skirmished until the 1960s. George Bernard Shaw wrote letters to newspapers supporting writers who split infinitives. Raymond Chandler complained to the editor of The Atlantic Monthly after a proofreader changed Chandler’s split infinitives:

“When I split an infinitive, God damn it, I split it so it will remain split.”

After the 1960s, authorities relaxed the rules about splitting infinitives.

Split decision: Modern English usage

Today’s grammar gurus agree that it’s fine to split an infinitive.

Why split infinitives? Among the arguments for infinitive-splitting:

1. It’s a non-issue in the first place. Keeping the “to” next to the “go”? Not important. As Otto Jespersen, author of Growth and Structure of the English Language, writes:

“‘To’ is no more an essential part of an infinitive than the definite article is an essential part of a nominative, and no one would think of calling ‘the good man’ a ‘split nominative.'”

2. It’s awkward not to split them. “Boldly to go where no man has gone before” just sounds weird. As James A. W. Heffernan and John E. Lincoln, authors of Writing: A College Handbook, 4th ed., write:

“An infinitive may be split by a one-word modifier that would be awkward in any other position.”

3. It’s clearer to split them. To make our copy clear, we place adverbs next to the verb they modify. Move the adverb, and you change the meaning. Take this sentence:

“She decided to gradually get rid of the kimonos she had collected.”

Move “gradually” to avoid splitting the infinitive, and you make the sentence wrong:

“She decided gradually to get rid of the kimonos she had collected.”

As H. W. Fowler, author of Fowler’s Modern English Usage, writes:

“Has dread of the split infinitive led the writer to attach the adverbs … to the wrong verbs, and would he not have done better to boldly split both infinitives, since he cannot put the adverbs after them without spoiling his rhythm?”

Theodore M. Bernstein, author of The Careful Writer, agrees. He writes:

“The natural position for a modifier is before the word it modifies. Thus the natural position for an adverb modifying an infinitive should be just after the to … [T]he split infinitive is often an improvement.”

And George Oliver Curme, Sr., author of Grammar of the English Language, writes that the split infinitive:

“ … should be furthered rather than censured, for it makes for clearer expression.”

Split personalities

I, for one, am an infinitive-splitter who splits infinitives with abandon.

Besides the arguments expert grammarians lay out for splitting infinitives, there’s another one: Split infinitives sound contemporary and conversational, more like busy business people than nagging English teachers. We reach readers by using the language they use, not by adhering to each formal rule of English composition.

Besides, I’d far rather my clients and colleagues worry about substantive writing issues — positioning their messages in the readers’ best interest, organizing arguments clearly and lifting ideas off the page or screen with display copy, for instance— than concern themselves with writing “rules” that have long outlived their heydays.

As Fowler and Fowler, authors of The King’s English, write:

“The ‘split’ infinitive has taken such hold upon the consciences of journalists that, instead of warning the novice against splitting his infinitives, we must warn him against the curious superstition that the splitting or not splitting makes the difference between a good and a bad writer.”

Consider yourself warned: Whenever it makes your sentence clearer, more elegant and more conversational, it’s more than OK to boldly split infinitives.

___

Source: “Split infinitive,” Wikipedia

Leave a Reply