Story structure affects readability scores

When you organize your copy logically, readers can read it more easily and get more out of it.

Or so says Bonnie J. F. Meyer, Ph.D., professor of Educational Psychology at Penn State University. She completed a five-year research project for the National Institute on Aging to find out what helped adults understand and remember what they’d read.

One element that made a big difference: the structure of the piece.

Ya gotta schemata

The reason: People have mental frameworks — aka schemata — that they’ve built through experience and instruction. These mental frameworks provide a skeletal structure for organizing information as they read. (Anderson, 1977; Rumelhart, 1975)

The clearer the writer’s framework, the easier it is for readers to place new information into their own schematas. Otherwise, information just comes across as a list of facts, which people can only recall through rote memorization.

Here are three ways, according to Meyers, that you can use structure to help people read your piece faster and remember it longer:

1. Follow a “topical plan.”

People read faster and remember more information that’s logically organized than they do when the same information is disorganized. (Kintsch, Mandel and Kozminsky, 1977)

Help them read faster. In one study, for instance, researchers gave half of the participants 1,400-word narrative passages and asked them to write a summary. The other half read the same information but with the content scrambled.

The summaries were much the same, but the scrambled versions took much longer to read. Readers needed the extra time to unscramble the content.

Help them remember longer. In another study, junior college students read two texts. Then they wrote down whatever they remembered, first right after reading, then again one week later.

Those who recognized and used the author’s structure to organize their memories retained far more content. They remembered the main ideas especially well, even a week later, and recovered more specific details, as well.

Those who didn’t use the author’s structures made disorganized lists of seemingly random ideas and couldn’t recover either the main ideas or the details very well. (Meyer, Brandt and Bluth 1980)

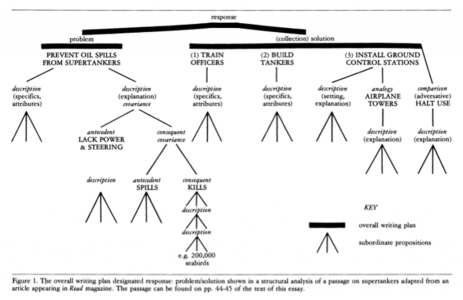

Think like a tree and leaf. Meyer proposes a tree-like structure of “nested hierarchies.” Put your main topics at the top, then drill down to more details in the branches. Here’s her structure for a piece about problems with oil tankers and four solutions:

Five structures. For the upper levels of the tree, Meyers suggests, you’ll probably use one of five structures:

| What | How | Example |

| Antecedent and consequence | Show cause and effect, if … then. | A bylined editorial may use this approach. |

| Comparison | Present two or more opposing viewpoints. | Political speeches often use this approach. |

| Description | Develop the topic by describing its component parts, such as attributes, specifications or settings. | Newspaper articles, for instance, explain who, what, when, where, why and how. |

| Response | Organize by remark and reply, question and answer or problem and solution. | Case studies focus on problem, solution, results. |

| Time-order | Relate events or ideas chronologically. | Company profiles often use this approach. |

The descriptive plan, the one used by newspapers, is least effective at helping people remember, according to Meyer’s early research. In two studies, participants were more likely to remember information from comparative and antecedent/consequence pieces than from descriptive stories — both immediately after reading and again a week later.

Using a solid structure is always essential. But it’s particularly important if you’re writing to younger readers, adults with lower reading skills and people who are unfamiliar with the subject.

2. Show the parts.

Average students remember more from stories that include “signaling” devices — display copy and transitions — than from those that don’t. Better students don’t need the signals as much, Meyer says; worse students may be lost no matter what help the writer gives them. (Meyer 1979)

So once you’ve organized your copy, use formatting and display copy to clarify the structure and hierarchy of your piece. Try:

- Headlines

- Subheads

- Underlining

- Italics

- Bold face

3. Show the relationships among and between facts.

The other type of signaling is within the text. Signaling includes:

- Previews, introductions

- Summaries

- Topic sentences

- Transitions

These signals remind readers what kind of structure they’re reading.

“If we encounter thus, therefore, consequently and the like, we know that the next statement should follow logically from whatever has already been presented,” Meyer says.

“If we see nevertheless, still, all the same or the like, we must be prepared for a statement that reverses direction.”

Help readers remember. In one study, a group of junior college students read a problem-solution piece about supertankers that included transitions. Another group read the same piece with the signaling deleted.

The deletions had no effect on the ability of the best or worst students to remember what they’d read. But those signals did make a difference for average readers. With the signaling, the average folks remembered more and organized the information better. (Marshall 1976, Meyer 1975)

Let form follow function. The structure and signals you choose will affect your readers’ understanding of the piece.

- Big picture: In one study, half of the participants read a comparison piece that signaled the structure with transitions like in contrast. Half read the same copy but without the structural cues. Those who got the signaling devices remembered the causal and comparative relationships but few of the details.

- Little picture: In another study, half of the participants read a time-ordered piece with transitions like early last century and soon after that. The other half read the same piece without the transitional phrases. Those who saw the transitions remembered the details very well but not the comparative and causal logic.

What do you want your readers to learn and remember? Let that goal drive your structural choice.

___

Source: Bonnie J. F. Meyer, “Reading Research and the Composition Teacher: The Importance of Plans, College Composition and Communication, Vol. 33, No. 1 (February 1982), pp. 37-49

Leave a Reply