Make readers’ brains light up

After I presented a Make Your Copy More Creative workshop recently, an attendee pulled me aside. “The speeches I write are just 20 minutes long,” he said. “I can’t afford to make room for anecdotes, metaphors and wordplay.”

I told him he couldn’t afford not to make room for creative elements — that those may well be the only parts of his speech his audience listened to.

That conversation reminded me of an old joke among professional speakers:

“When should you use humor in a speech?” a young speaker asks an experienced orator.

“Only when you want to get paid,” the veteran answers.

The same thing is true for writers: When should you use creative material in your message?

Only when you want your audience to pay attention.

Attention is Job 1.

Grabbing attention is one of the four key responsibilities of a business communicator. After all, our job description is to get readers to:

- Pay attention to our messages

- Understand them

- Remember them

- Act on them later

And that takes creative story elements.

It’s true. Creative material:

1. Grabs attention.

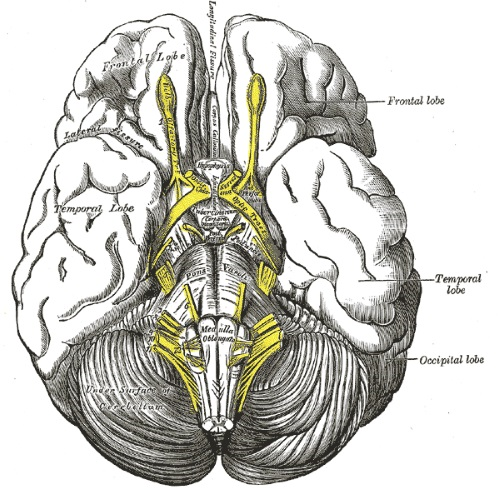

Meet your Broca’s area — a small part of your brain located in the frontal lobe of your left cerebral hemisphere. It’s your body’s language control center.

You can thank your Broca’s area for helping you sort through the equivalent of 174 newspapers, ads included, that you and everybody else gets bombarded with each day — without having to process every word.

Remember that old Far Side cartoon by Gary Larson?

What we say to dogs: “Okay, Ginger! I’ve had it! You stay out of the garbage! Understand, Ginger? Stay out of the garbage, or else!”

What dogs hear: “Blah blah Ginger blah blah blah blah blah blah Ginger blah blah blah blah blah.”

Your Broca’s area is Ginger: not paying much attention to most messages — until something really interesting comes along.

Well-worn phrases like “a rough day” are so familiar they don’t activate your Broca’s area. Plain old ‘splainin’ doesn’t do anything for it either.

But creative techniques like wordplay activate Broca’s area (PDF).

Want to cut through the clutter of competing messages (PDF)? Activate readers’ Broca’s area with wordplay and other creative techniques.

2. Keeps that attention longer.

Here’s a finding that will surprise absolutely nobody: Creative sentences encourage reading more than boring ones, according to 1986 research by Suzanne Hidi and William Baird.

Hidi and Baird studied creative sentences like these:

- Adult wolves carry food home in their stomachs and bring it up again or regurgitate it for the young cubs to eat — the wolf version of canned baby food.

- Thomas Edison became the most famous inventor of all time even though he left school when he was only 6 years old.

- A canary can also bluff by playing dead. A frightened canary may go limp in someone’s hand.

Here, in contrast, is the first sentence in the latest news release listed on BusinessWire right now:

Did you read to the end? Of course not.

And that’s the deal. Creative material keeps attention longer — throughout the passage or the piece and over time. Indeed:

- Ads with metaphors in the headline get read more completely than those with literal headlines, according to an archival study of 854 ads.

- Newspaper articles using the storytelling structure are more likely to pull readers across the jump that those using the inverted pyramid, according to research by the American Society of News Editors.

- A blog post with a creative lead drew 300% more readers and 520% more readingthan one with an abstract lead, according to an A/B test by Groove HQ.

Want people to read more of your message? Keep their attention with creative elements.

3. Makes readers’ brains light up.

Think of description as virtual reality:

- Describe a scent, and your readers’ primary olfactory cortexes light up.

- Describe texture, and you activate their sensory cortexes.

- Describe kicking, and not only do you stimulate their motor cortexes, but you stimulate the specific part of the motor cortex responsible for leg action.

“Brain scans are revealing what happens in our heads when we read a detailed description, an evocative metaphor or an emotional exchange between characters,” reports Annie Murphy Paul in “Your Brain on Fiction” for The New York Times. “Stories, this research is showing, stimulate the brain and even change how we act in life.”

Paul reports on new studies that show how description, metaphor and storytelling can make readers smell scents, feel textures, experience action — even understand others better.

| Look and feel | |

| These textural metaphors lit up the sensory cortex … | … while these literal phrases did not |

| She drove a hard bargain | She drove a good bargain |

| Life is a bumpy road | Life is a challenging road |

| He is a smooth talker | He is persuasive |

| This steak is rubbery | This steak is overcooked |

| He had leathery hands | He had strong hands |

But write abstractly — aka, the way we usually do in business communications — and readers’ brains remain dark.

Want to stimulate some brain activity around, say, your CEO’s latest strategy or that brilliant Whatzit you’ll be releasing later this month?

Creative material is the answer.

4. Makes people read more carefully.

A hand shoots up in my Art of the Storyteller workshop, where we’ve been talking about wordplay.

“But,” the communicator says, “don’t you risk confusing people with wordplay?”

Well, yes, I said. Yes, you do. And that’s part of the point.

When readers encounter wordplay, they first try on the literal meaning of the words. When that doesn’t work, they seek alternative meanings.

Same thing happens with metaphor.

Because readers spend extra time processing wordplay (PDF) and metaphor, they pay closer attention to your message, understand it more fully and remember it longer.

Some of the power of metaphor and wordplay, researchers believe, comes from readers’ delight in figuring out the right answer.

Call it the pleasure of the text. That pleasure may cause them to slow down and savor your message.

5. Gets readers to linger over your message.

Readers in one study read 479 words a minute on average. But they read only 394 words a minute — 18% more carefully — when reading the passages they most enjoyed.

“My purpose is to make what I write entertaining enough to compete with beer.”

Anonymous

In other words, they savored the copy, reading almost 18 percent more slowly. Call it ludic reading — from the Latin ludo, or “I play.”

Pleasure reading is a form of play, writes researcher Victor Nell, author of Lost in a Book: The Psychology of Reading for Pleasure. He studied 245 subjects during six years to learn how people respond to writing they enjoy.

While he can’t say for sure why people read the passages they enjoy most more slowly, he thinks it’s because they move from skimming to savoring.

Researchers estimate that people can read as fast as 600 to 800 words a minute while still understanding each thought fully. (That’s known as “rauding” among reading experts.)

Often, though, people “bolt” the text, or just skim for an overview.

But when they come upon passages they enjoy, readers stop bolting and start paying closer attention to the copy.

So when should you use creative material? Only when you want your audience members to savor your message.

Are you using creative elements to draw attention to your message? Or are you trying to light up readers’ brains with the same old blah-blah-blah?

____

Sources: “Reading Creates ‘Simulations’ In Minds,” NPR, Jan. 31, 2009

Véronique Boulenger, Beata Y. Silber, Alice C. Roy, Yves Paulignan, Marc Jeannerod and Tatjana A. Nazir, “Subliminal display of action words interferes with motor planning: A combined EEG and kinematic study,” Journal of Physiology-Paris, Vol. 102, Issues 1–3, January-May 2008, pp. 130-136

Steven Cherry, “This Is Your Brain on Metaphor,” IEEE Spectrum, April 6, 2012

Michael Chorost, “Your Brain on Metaphors,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, Sept. 1, 2014

Roger Dooley, “Your Brain on Stories,” Neuromarketing, Jan. 21, 2010

Steve Frandzel, “Metaphors Make Sens(ory Experiences),” The Academic Exchange, Emory University, May 11, 2012

Julio González, Alfonso Barros-Loscertales, Friedemann Pulvermuller, Vanessa Meseguer, Ana Sanjuán, Vicente Belloch, and Cesar Avila, “Reading ‘cinnamon’ activates olfactory brain regions,” NeuroImage, May 2006

Wray Herbert, “The Narrative in the Neurons,” We’re Only Human, Association for Psychological Science, July 14, 2009

Simon Lacey, Randall Stilla and K. Sathian, “Metaphorically feeling: Comprehending textural metaphors activates somatosensory cortex,” Brain & Language, Vol. 120, Issue 3, March 2012, pp. 416–421

Raymond A. Mar, “The Neural Bases of Social Cognition and Story Comprehension,” Annual Review of Psychology, Vol. 3, 2011, pp. 103-134

Victor Nell, “The Psychology of Reading for Pleasure: Needs and Gratifications,” Reading Research Quarterly, Vol. 23, No. 1 (Winter 1988), pp. 6-50

Annie Murphy Paul, “Your Brain on Fiction,” The New York Times, March 17, 2012

Pradeep Sopory and James P. Dillard, “The Persuasive Effects of Metaphor: A Meta-Analysis,” Human Communication Research, July 2002

Leave a Reply