Hourglasses, spirals, oranges and more

“When you have news, report it,” advises Roy Peter Clark, Poynter Institute senior scholar. “When you have a story, tell it.”

That’s where hourglasses and spirals come in.

But before we get to them, let’s do a quick primer on two of the most popular story structures.

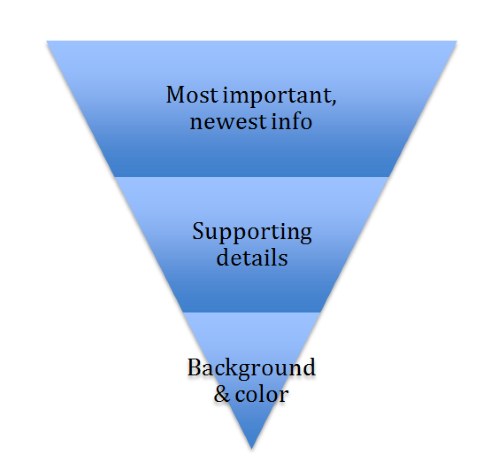

Inverted pyramid

You remember the inverted pyramid.

This hierarchical news structure moves from the most newsworthy facts to least important supporting details. It’s designed to be cut from the bottom — either by busy editors in a hurry or busy readers in even more of a hurry.

Use it when you have news to report — and when you don’t care whether the reader reads past the first paragraph.

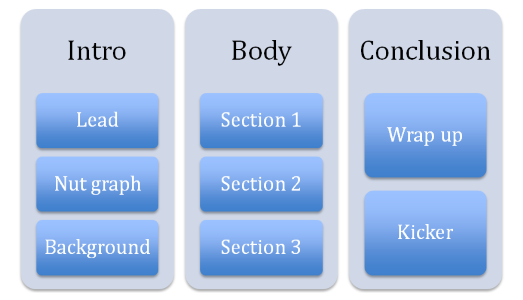

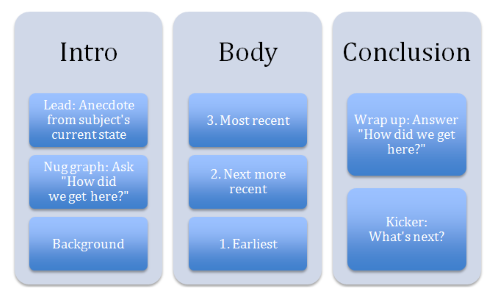

Feature-style story structure

And you know the feature-style story structure.

Its beginning-middle-end design was created to grab and keep reader attention. It uses human interest, anecdote and other colorful, concrete details to make the story interesting as well as informative, and to show as well as tell.

Use it when you have a story to tell instead of facts to deliver.

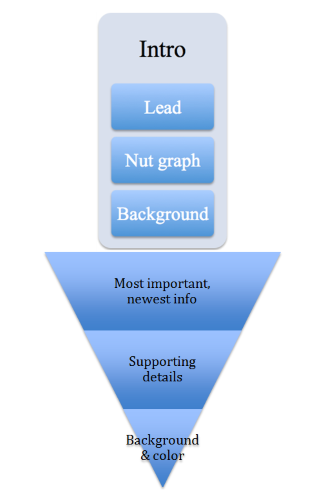

Feature-news release hybrid

Then there’s a new structure I’ve noticed in press releases recently.

It has a feature head and an inverted pyramid tail. The beauty of this beast is that It brings the story to life at the top with a feature lead, nut graph and background section. Then, once it has the reader’s attention and established the story, it delivers the details in a hierarchical, most-important-to-least-important body.

Use it when you have a story that would benefit from a feature lead but that needs a just-the-facts-ma’am resolution.

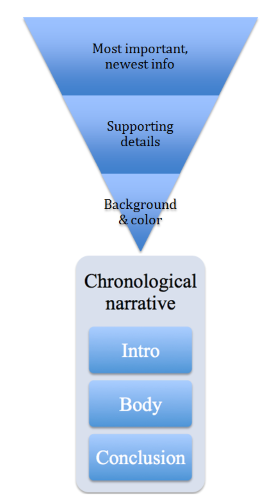

The hourglass

The hourglass is another feature-news hybrid, but this one puts the pyramid up top, then follows up with a feature format. Use it when you need to report news but also have a story to tell.

Here’s how it works:

- Deliver the facts in a couple of paragraphs in an inverted pyramid. Maybe “we learn that a man shot a police officer in the leg, ran into a house, held a boy hostage for eight hours, surrendered without harming the boy, and was finally arrested,” writes Roy Peter Clark, Poynter Institute senior scholar.

- Take a turn. Write a one-sentence transition into the narrative: “‘Police and witnesses gave the following account of the dramatic incident,'” Clark suggests.

- Tell the story. Write a chronological narrative that develops the story with all its colorful details.

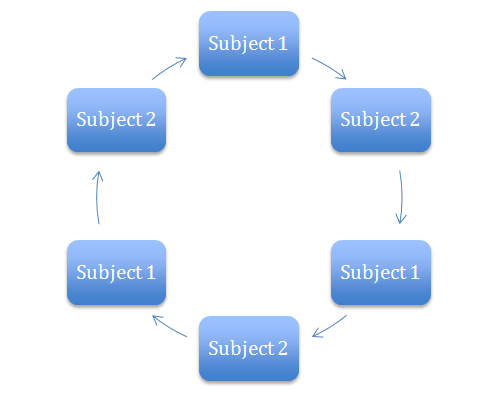

The spiral

This structure makes sense when you have a story to tell (or news to report) about two equally important subjects — maybe a doctor who developed a technique and the first patient to undergo it, suggests David Fryxell, former editor of Writer’s Digest.

It doesn’t make sense to tell the doctor’s story first, the follow up with the patient’s. Instead, weave the two stories together into a spiral. You can organize the facts hierarchically like a pyramid or use a beginning-middle-end feature approach.

Maybe you’ll describe:

- Basic details about the technique

- Basic details about the patient

- How the doctor developed the technique

- How the patient decided to try it

- More about the doctor

- More about the patient

Rewind

Using this structure, you tell the story backward, from effect to cause.

Stuart: A Life Backwards, for instance, hits the rewind button to show “what murdered the boy I was.” Using reverse chronology, author Alexander Majors documents how a “happy, lively little lad” ended up living a life of chaotic homelessness.

The movie “Memento” and this video also use reverse chronology.

How could you use this approach to show effect, then cause — or to reverse your audience members’ notions about your subject?

Organic structures

Form follows function in an organic format. You might organize a piece about Twitter as a series of time-stamped tweets, for instance.

John McPhee, master of narrative nonfiction, has made an art of the organic form. The structure of his book Oranges, for instance, parallels the life cycle of the fruit. And in The Search for Marvin Gardens, he uses the structure of the Monopoly board to contrast the megabucks game with the down-in-the-dumps reality of Atlantic City.

And Chip Scanlan, senior faculty-writing at The Poynter Institute, suggests organizing your copy into a series of:

- Tarot cards

- Locations in a person’s home

- Classifieds, help-wanted ads or personals

Does your story suggest a structure? If so, lucky you. That’s probably the strongest organizational form of all.

___

Sources: Roy Peter Clark, “Two Ways to Read, Three Ways to Write,” The Poynter Institute, January 1998

David A. Fryxell, “Rebuilding the Pyramid,” Writer’s Digest, November 2004

Chip Scanlan, “Reporting the past: writing the investigative memoir,” Nieman Narrative Conference, Dec. 6, 2003

Leave a Reply