Read it; feel it

Read the words coffee, camphor or eucalyptus, and the part of your brain most closely related to the sense of smell responds. Read the words bingo, button or bayonette, and they don’t.

The words you choose not only have the power to change your readers’ minds. They can also change their brains, according to new neurological research.

“Brain scans are revealing what happens in our heads when we read a detailed description, an evocative metaphor or an emotional exchange between characters,” reports Annie Murphy Paul in “Your Brain on Fiction” for The New York Times. “Stories, this research is showing, stimulate the brain and even change how we act in life.”

Paul reports on new studies that show how words make us smell scents, feel textures, experience action — even understand others better.

1. The nose knows.

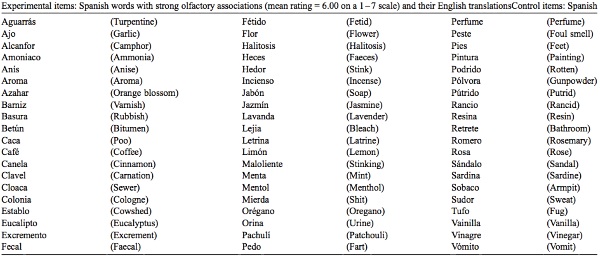

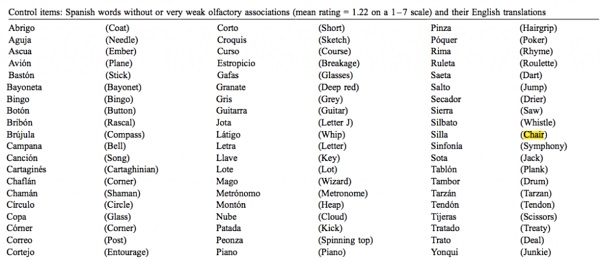

In 2006, researchers in Spain used a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) machine to scan participants’ brains. Then they asked participants to read words describing odors — rancid, resin and oregano, for instance — as well as scent-neutral words, like circle, short and sketch.

When participants read the words describing odors, their primary olfactory cortex — the part of the brain most closely associated with the sense of smell — lit up. When they read the neutral words, this region remained dark.

Bottom line: Readers have a physical response to sensual description. Want to make your readers’ brains light up? Use descriptive language.

Smell what I say

2. Feel the burn.

Three researchers at Emory University used fMRI scans on subjects who read phrases involving texture.

When the subjects read textural metaphors — Life is a bumpy road, for instance, or He is a smooth talker — the sensory cortex, which is responsible for perceiving texture through touch, became active. When they read neutral phrases with the same meaning — Life is a challenging road or He is persuasive — the sensory cortex remained dark.

|

Look and feel |

|

| These texture metaphors lit up the sensory cortex … | … While these literal phrases did not |

| She drove a hard bargain | She drove a good bargain |

| That man is oily | That man is untrustworthy |

| Life is a bumpy road | Life is a challenging road |

| He is a smooth talker | He is persuasive |

| This steak is rubbery | This steak is overcooked |

| He had leathery hands | He had strong hands |

| She is a bit rough around the edges | She is a bit impolite |

| He fluffed his lines | He forgot his lines |

| He is a smooth operator | He is a suave guy |

| She has a bubbly personality | She has a lively personality |

| The logic was fuzzy | The logic was vague |

| She gritted her teeth | She ground her teeth |

| She decided to rough it | She decided to go without |

| She is sharp-witted | She is quick-witted |

| It was a hairy situation | It was a precarious situation |

| This soda is flat | This soda lacks taste |

| The wind is sharp | The wind is cold |

| The operation went smoothly | The operation went successfully |

| She has steel nerves | She is very calm |

| That book is full of fluff | That book is full of nonsense |

| His step was springy | His step was energized |

| She gave a slick performance | She gave a stellar performance |

| The clouds were fleecy | The clouds were white |

| His voice was silky | His voice was calm |

| His eyes went fuzzy | His eyes went blurry |

| The punch is spiked | The punch is alcoholic |

| She bristled with anger | She shouted with anger |

| He is wet behind the ears | He is a naïve person |

| He is on a slippery slope | He is getting out of control |

| She is soft-hearted | She is kind-hearted |

| He is a greasy politician | He is a corrupt politician |

| He has an uneven temper | He has an uncertain temper |

| His face was stony | His face was stoic |

| He has a slimy personality | He has a deceitful personality |

| The movie made her mushy | The movie made her cry |

| His manners are coarse | His manners are rude |

| She is a bit edgy | She is a bit nervous |

| He was a crusty old man | He was an irritable old man |

| She has a dry sense of humor | She has an odd sense of humor |

| She had a rough day | She had a bad day |

| He is a softie | He is a pushover |

| The singer had a velvet voice | The singer had a pleasing voice |

| He was a slippery customer | He was an awkward customer |

| His skin prickled with anticipation | His skin went cold with anticipation |

| She asked a pointed question | She asked a relevant question |

| She has an abrasive personality | She has an unpleasant personality |

| Her voice was scratchy | Her voice was hoarse |

| The criticism was blunt | The criticism was straightforward |

| The book was mushy | The book was sentimental |

| He had a rugged face | He had a manly face |

| It was a polished performance | It was a flawless performance |

| Her voice was grating | Her voice was harsh |

| She looked sleek | She looked stylish |

| His voice was gravelly | His voice was low |

3. And … action!

Cognitive scientist Véronique Boulenger of the Laboratory of Language Dynamics in France studied how people’s brains reacted to phrases conveying motion.

When subjects read action verbs like write and throw, their motor cortexes — the part of the brain that coordinates the body’s movements — lit up. When they read nouns like mill and cliff, their motor cortexes stayed dark.

Even more interesting, one part of the motor cortex lit up when subjects read about arm movement, while a different part did when they read about leg action.

4. In character

Just as the brain treats descriptions of physical sensations and action as if they were real, it also treats written interactions among people as if they were real social encounters.

Raymond Mar, a psychologist at York University in Canada, analyzed 86 fMRI studies published last year in the Annual Review of Psychology. His conclusion: As we practice understanding people when we read, we become better at understanding them in reality.

Narratives, Paul writes, help us “identify with subjects’ longings and frustrations, guess at their hidden motives and track their encounters with friends and enemies, neighbors and lovers.”

Virtual reality

Bottom line?

“The brain, it seems, does not make much of a distinction between reading about an experience and encountering it in real life,” Paul writes. “In each case, the same neurological regions are stimulated.”

Keith Oatley, an emeritus professor of cognitive psychology at the University of Toronto and a published novelist, agrees.

Reading, he told Paul, is a reality simulator that “runs on minds of readers just as computer simulations run on computers.”

For writers, that means that the words you choose aren’t just words. They can also be things, experiences — even emotions. Choose them well.

___

Sources: Annie Murphy Paul, “Your Brain on Fiction,” The New York Times, March 17, 2012

Julio González, Alfonso Barros-Loscertales, Friedemann Pulvermuller, Vanessa Meseguer, Ana Sanjuán, Vicente Belloch, and Cesar Avila, “Reading ‘cinnamon’ activates olfactory brain regions,” NeuroImage, May 2006

Simon Lacey, Randall Stilla and K. Sathian, “Metaphorically feeling: Comprehending textural metaphors activates somatosensory cortex,” Brain & Language, Vol. 120, Issue 3, March 2012, pp. 416–421

Véronique Boulenger, Beata Y. Silber, Alice C. Roy, Yves Paulignan, Marc Jeannerod and Tatjana A. Nazir, “Subliminal display of action words interferes with motor planning: A combined EEG and kinematic study,” Journal of Physiology-Paris, Vol. 102, Issues 1–3, January-May 2008, pp. 130-136

Raymond A. Mar, “The Neural Bases of Social Cognition and Story Comprehension,” Annual Review of Psychology, Vol. 3, 2011, pp. 103-134

Leave a Reply